BY MIKE MUTHAKA

“We create. We’re actually gods. We build cities. We design. We do art. We can shape the world.”

Joy Wangu Munge, 22, smells like cherry blossom perfume. She’s had a long week. She’s a third year architecture student at UoN, and there’s a shiny smudge of sweat on her neck when she enters the ADD building along State House Road. It’s Saturday, 2 p.m.

She’s carrying a bag of tin-foiled fried potatoes, along with an apple, an umbrella and a leather-bound notebook. Today she was meant to go swimming with a friend. But the friend cancelled, and Joy let out a sigh of relief.

“I told her I’ll see her tomorrow instead,” she says. “I just want to stay home.”

Joy has a nerdy look about her, made even so by her Harry Potter specs and the gentleness of her movements. She’s like a book, she opens up more as we go along; up the flight of stairs leading to the architecture studios, every step like a page-turn, every breath like a well-placed comma. She opens herself to the day’s possibilities. But she doesn’t feel like an open book.

When we get to the studio, she fetches for the apple and takes a small bite. Drops of juice fall to her shirt. Then she takes out her journal and starts reading from it.

“Maybe I don’t write because I’m running from introspection. I ask myself, why did I journal through high school? Why am I journaling now? How important is it for me?

“I’m growing slowly. I’m still learning lessons in living outside fear and beating procrastination, my biggest nemesis. I’m learning accountability, but more so freedom in responsibility.”

She takes another bite of the apple.

“Living on my own terms. Relishing late mornings and late nights.”

She regards her own writing with the amusement of a kid in a candy store. Then she promptly shuts the journal and turns to me.

“I wake up at seven every day, but I start my day at nine. And I should feel guilty for it, coz, like, we all have the same 24 hours.” She giggles. “But I like it. This glorification of the struggle is bullshit. Glorification of being busy, always having somewhere you are running to. Ati sijui ‘I have a meeting’. Kenyans love meetings,” she says with a smile.

Joy wants to save the world. She gives a damn about the environment. She’s a feminist.

“There are a lot of feminist theories I still have to learn. And I’m a socialist. Well I also have a lot of reading to do [on socialism], but, looking at how resources have been distributed in this capitalistic era. And you see that it’s fucking wrong. It’s fucked up that 5% of the population own 95% of the resources.

“So, it’s about fixing the system. I wouldn’t even say I’m a socialist yet. But I’m a believer that the world needs to change for the better. Because if the world isn’t built for its people, isn’t that messed up?

“I don’t know how I’m going to change the world. Maybe I’ll do it through my architecture, designing spaces and buildings for communities, for women, for refugees. Sometimes I think of rebuilding Syria and war-stricken countries. Sometimes I think of just becoming a teacher. Like a school-of-life kind of thing, where people can learn that things need to change. We shouldn’t be complacent to the way things are.”

She offers me the apple. It’s juicy, and it melts in my mouth. Then I ask, “Do you believe the story of creation? The apple, the forbidden fruit and all that?”

“I don’t believe it was an apple,” she says. “I mean, ugh, you know how the Bible is full of imagery? People are always interpreting these things. Who said it was an apple?”

“Could have been a guava?” I say.

“Guavas are maperas?” she asks. “I think they’re maperas. If they are, it couldn’t have been. It also couldn’t have been a mango. It was probably an avocado, because avocadoes are nasty.”

She chuckles.

“I don’t think it meant a fruit fruit,” she continues. “It could have been something else. Weird stuff. Si people talk about vaginas like they’re fruits? But I’d feel very bad if sex was the cause of sin. That’s fucked up. The punishments seemed to be aligned to sex lives.

“We already have such a screwed-up outlook on sex, like it’s the most disgusting thing in the world. That outlook has caused most of our problems. Like, people can’t talk about sex objectively, without shame. Women go through their entire lives without understanding that sex is not just for men. Many women go through their entire lives without getting an orgasm. So yeah, it would be bad.”

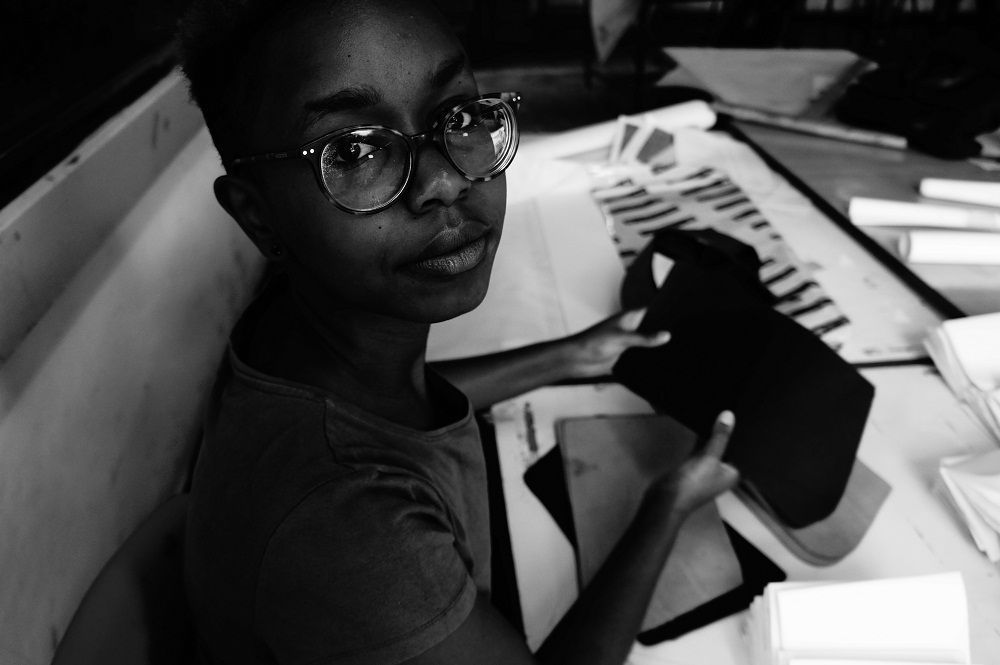

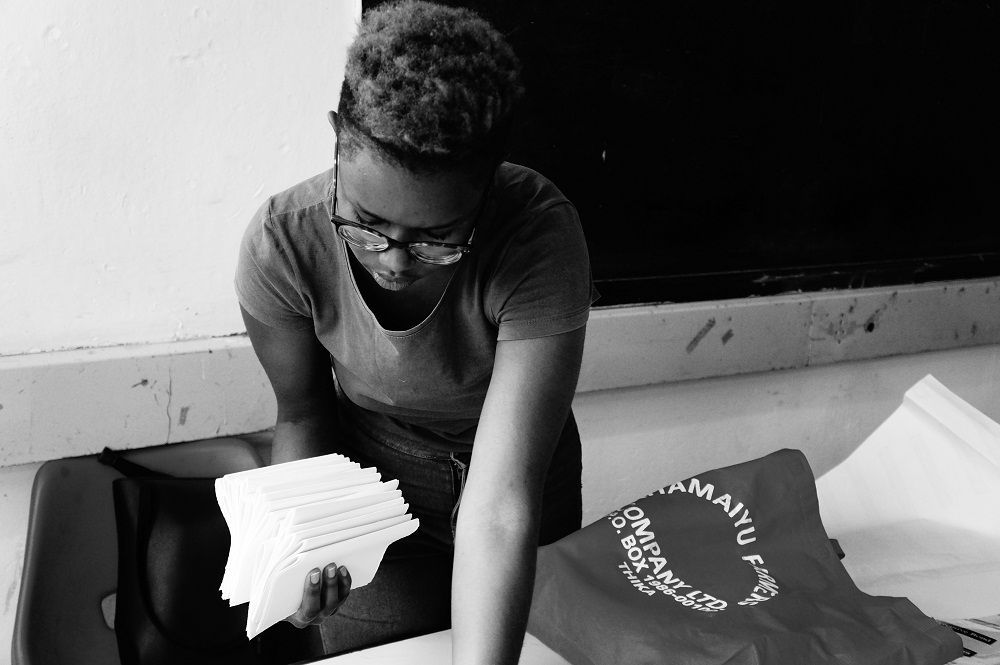

Joy has an easy laugh. During our conversation, she speaks in short pauses, mostly because her deft hands are busy folding and cutting sheets of paper. She recently got recruited into a friend’s company, Erregatti, which is an art, design and architecture outfit. And they’re making books today. Joy tells me making books relaxes her.

We’re seated in an airy corner in the sixth years’s architecture studio. The window overlooks a stone balcony with some graffiti. Our table is strewn with arch stuff – building plans detailed from floor to ceiling, papers rolled into cylinders, and a lone brown T-squaree.

Also sitting through the interview is Moses, Joy’s pal, another member of Erregatti. Moses handles the leatherwork. He gets the leather from Kariokor, which they use as book covers. Each book sells at 3K, making one takes about 40 minutes.

The book making is underway. Joy uses a ruler to flatten the folds, then she rips the paper right down the middle. She does the same for each half. Someone else will make the holes through which the threading will be done. The paper is then knit into the leather. Finally, they install a strap.

The notebook in Joy’s bag is a product of Erregatti.

I ask if I can see it.

She pulls it out of her bag. The book is scribbled with architecture class notes and quotes from famous architects. Joy’s handwriting is small and wavy. As I leaf through the pages, two abstract water-colour paintings fall out. I point to one and ask, “What is this?”

“It was supposed to be Nairobi, but it was more about the colour for me than the actual painting. I like bright things. And I love warm colors. Greens and yellows and oranges. But I never found a language.

“I think that’s why I abandoned painting. I wasn’t good enough. Like the way Pablo Picasso paints, or the way Basquiat would paint. You know? They had a way, a language. I don’t think they were trying to paint like someone. And I just got tired, as I do with every other thing. I guess it’s something to do with my personality.”

Joy is the last born in her family. She has two older brothers, Kenneth, 36, and Edward, 34. Kenneth is a medical researcher. Edward is a dentist. Both of them are married and have kids. Kenneth still hasn’t quite moved out. He’s built a simba outside his folks’ place. His wife and kids are down in Coast. He goes to see them every other week. It was Kenneth who bought Joy her first architecture book, while he was studying in the U.K.

“I love arch because I get to read a lot about different stuff. Like, you’re required to read about philosophy and fine art, and, like, if you’re designing a hospital you kinda have to learn about how people work. Psychology. I like that. ‘Cause I like to read.

“We never get bored in the studio. Arch is like the silent leader. You rarely hear people talking about how a building makes them feel. The reason why people love the streets of Paris is because of that planning; the buildings, the styles. That’s architecture. It’s what makes things great. Like it’s not so loud, not as loud as fashion.”

Incidentally, fashion is something Joy wants to explore as well. In the corners of her mind, she sees herself as a stylist or the editor of a fashion magazine.

“I also imagine working for an NGO, using my architecture to build communities. Other times I picture myself as a housewife married to a rich man who doesn’t want kids, and I can paint all day. And host brunches.” She chuckles.

In 2018 Joy started making journals, to sell. Then she suddenly stopped. I ask why.

“Logistics, and if I was to make books, I’d want them to be eco-friendly. Also, I hadn’t thought it out well. I wasn’t making profit. I was buying books, but the covers I really wanted were from South Africa. So, I couldn’t get regular supply. Just, a lot of logistics.” She grins. “Si that’s what business people always say? Logistics.

“I’d buy the book, then I’d cut the fabric to fit the book. Glue the fabric onto the cover. And, yeah. It wasn’t difficult. My brother got me the fabric. I wanted to…”

She sighs and rolls her eyes. “Tsk. Men. I told my brother to bring me fabric and he bought me handkerchief sizes. I wanted the big ones. Plus, they were also very stiff.

“You know there’s this thing ati, say, have one hobby that makes you money, a hobby that keeps you fit and a hobby that…that? What’s the third one? Sijui. But every time a hobby of mine turns into a money-making situation I don’t really like it. I lose the hobby. But I don’t think that will be the situation when I start making clothes.”

Still, Joy insists she’s not an artist.

“I don’t like to be recognized as an artsy person.”

“What do you like being recognized as?” I ask.

“As Joy. I’m my own person. Because once you start talking about one thing, it shuts up so many doors for you. And there’s a bad stereotype of people who are artsy that I don’t like.”

Her voice trails away. She shreds more paper.

“Uuh, some become so stand-offish and they’re somewhat know-it-alls- and… in the name of art there’s a lot of mediocrity…a lot of, uuh…things that pass as art just because people know the right people, rather than actual art. So I just like to be defined as me.”

Joy is inspired by work ethic.

“He [Moses] inspires me. Beyonce inspires me. Rihanna inspires me. People who work smart and are still living.”

She also liked ‘Dance of the Jacaranda’, by Peter Kimani.

“He writes so beautifully it even made me want to cry. But he pissed me off at the end. He erased women’s stories. He actually said, ‘And the women, we don’t know what became of them, because as is…’”

She sighs again. “But he writes well. About how Africans speak with flavor. It’s so nice.”

Just as Joy says this, it starts to rain. She looks at the fat grey cloud, and says, “I didn’t carry a sweater. But I have an umbrella.”

She has to run. She’s meeting someone in Westy before she goes home. She takes out her phone and hails a boda. Meanwhile, Moses helps her to pack the sheets of paper.

The rider calls back almost immediately. Joy picks up. “Hello. Sema, uko? Oh, ushafika? Sawa. Uko side gani? YMCA? Sawa. Nipee dakika mbili nishuke.”

As she picks up her bag, I ask her what she hopes to achieve in 2019.

She says, “I want to go to Zanzibar. I want financial stability. To run more. And overcome procrastination. I want more Fenty make-up. I want to move out, and do my brows regularly, and take care of my skin. Oh, and spend less time in traffic.”

Joy walks out of ADD with a smug face and tired hands. The boda guy is waiting. When they meet, he says, “Na umekawia.”

And Joy, with a tongue in cheek, says, “Pole. Nilikuwa meeting.”

—-

Follow Mike on Instagram: mikemuthaka