BY FLORENCE BETT-KINYATTI

“Why did you choose to make bags, Benta?”

“I’d wanted to continue with doing shoes but lack of good quality soles led me to making bags, that was the easier option for me. Cause everything was available in Kenya – the leather, these fittings, the accessories of bones and horns, the fabric I use for the lining.”

“And what made you confident you could make bags?”

“I wasn’t!” Benta leans back in her working stool and laughs hard, her feet even leave the floor. She thinks back to February 2016, when she went into this business. “I wasn’t confident. I just landed here…. I don’t know. For me, once I’ve started thinking something, I do it without even doing the market research and all that. Ha ha. That’s how I ended up making many mistakes along the way. Make sure you do your research, don’t make a mistake and go in blind like me.

“So I thought about bags and I went ahead and created bags, but they were not really bags, they were like prototypes of bags. But I had to learn how to make patterns, that’s when I went to KIRDI to train me on how to make a pattern. [Kenya Industrial Research and Development Institute]

“KIRDI is a government-owned institute,” Benta carries on, “they train people and they deal with leather. I found a guy who accepted to train me outside KIRDI because it was cheaper working with him as…him than with him as KIRDI. He had his own workshop in Gikomba, that’s where we’d meet, he also makes bags and wallets, but I don’t know why he hides himself. He trained me for six gees but told me that I won’t be able to learn everything in a week. I told him I don’t have extra income,” Benta throws her arms over her head, palms out, as if she’s asking the world ‘why’, “I told him to train me everything he could, I really didn’t have an option.”

“What did he teach you?” I sip from my glass of water.

“He taught me how to make a pattern, how to make wallets, how to come up with such,” Benta lifts up a bag pack she’s still working on, “but it was more of theory because I didn’t have enough money for him to do the practical work. I had to be very keen to watch what he was doing on his machine, he was just talking, talking, talking. Heeh. YouTube also helped me a lot.”

“But by this time Mchungaji on QTV was still going on? You still had a salary from there?”

“Yes, it was. What happens in the acting industry is that you’ll work for a month then the salary might not come again for maybe three or four months, sometimes even a year, depending on the production. So it wasn’t really monthly income for me but I had a role. Yes, the one as a househelp with a Coasterian accent.”

Benta Wangui. 30 years. She’s the founder of BagWorld Leather, a company that makes leather products using authentic and locally-sourced leather. She makes bags mostly, both for guys and girls – bag packs, clutches, hand bags, travel bags, satchels, laptop sleeves. She also makes belts and wallets.

She sometimes stitches her products by hand, mostly it’s by machine.

Everything is made by order, and customized to your tastes and preferences.

Benta accessories her bags with specially handcrafted bones and horns, she sources them from artisans in Kibera.

Benta grew up in Malindi with her moms, pops and her big brother. Her folks are from Central though – Dad, Nyeri, Mum, Kirinyaga – it’s their grandpa that lives in Malindi. Benta and her family moved there when she was about four. (I think. Or I could be making that up, I’m not sure. But she moved there when she was pretty young.)

After sitting her final high school exam, Benta joined Mombasa Polytechnic for a diploma in analytical chemistry.

“My goodness, why did you pick such a course?”

“I honestly didn’t know what it was about.” Benta laughs. “Maybe because my Dad was like,” she points her finger into the air and speaks as a suburban African dad would, “‘You must take science, take analytical or mechanical engineering.’ So I was like, sawa, let me just go with analytical chemistry.”

Benta graduated in 2011, got a jobo in Mombasa as an inspector with a new-ish company called Quality Inspectors. Her JD was to measure radioactivity in all the products the company used to import, food and consumables and such like.

“Did you enjoy the work?”

“No, not really.” Benta twists her face up as if the memory of it is tickling her sinuses. “It was a boring job. Then it was Mombasa, I used to wake up at 10, go to work at 11, leave by 5 and we didn’t have many clients because it was new and there we many competitors. So I’d just sleep most of the time or watch YouTube. Ha ha. The only thing I enjoyed about my job was the free internet.”

She says, “I was getting around 20gees and I was very happy. But two years down the line, it hit me, like, What, that salary is so small. Ha ha. I asked them to increase it but they refused so I had to look for something else to do.”

Her happiness wisped away faster than those bills wisped away in her wallet at the end of every month.

Benta needed a plan B. A side hustle. A personal project. Just something – anything – to complement her salo. Right before she went to bed one night, she remembered that she can dance. And not just dance-infront-of-my-bedroom- mirror dance, but dance-like-a-professional dance – on stage, to a choreographed routine, with a troupe, in costume and to an overarching theme of production. Benta was going to sashay her way to extra cash in her pocket.

She two-stepped to Little Theatre, a theatre in Mombasa and joined a troupe. But because of poor management, inconsistent gigs and the hunt for the extra cash she desperately needed, Benta put aside her dancing shoes and auditioned for a role in one of the theatre’s plays. “It was the role of a sex worker,” she says, cracking a small smile, “but I didn’t get it, they told me I’d be a backup actress.” The lead actress fell off the grid and Benta took up the role but she didn’t like it.

Acting on stage wasn’t what it was cranked up to be – the directors yelled and scolded, they were impatient with her inexperience. She shrunk under the spotlight. Benta hang in there because she needed the cash and she was passionate to learn this craft. She grew to love it. (And it loved her back, the directors stopped yelling at her.) She became good at it and found happiness again. It’s actually the acting that would later and fully finance BagWorld. More on that later.

Benta moonlighted at the theatre as she quality inspected when the sun was nigh. She did this for two years to 2014, when she quit both jobs and relocated to Nairobi at the insistence of her pals.

“Had you been to Nairobi before?”

“Yes, but I used to pass through on my way to shagz.”

“And what were your feelings and your thoughts on moving here?”

“I had to ask for…” Benta trails off as her train of thought derails. “I had to inquire a lot, talk to people about me quitting my job. But everyone said,” she raises her voice to a falsetto, “‘Don’t quit! Where will you get money from?’” She chuckles. “But my instinct was on quitting, because I knew I’d never grow – I decided to follow my heart. I came to Nairobi with savings of 50 gees, I knew I could sustain myself but it wasn’t until I got here that I realized Nairobi is more expensive. I went to live with some friends in Pangani.”

Benta hadn’t even finished unpacking her suitcases when she was already on the ground doing legwork for her first biashara: she’d buy sandals for Sh200 from Kariokor, accessorise them by hand with beads and Ankara fabric, then resell them for Sh450.

She shut the business down in less than a month, though. “My clients were really complaining! Yes they loved the designs but the shoes were of poor quality – they’d wear the sandals for maybe two days then the sole tears off or something. It was creating a bad CV for me and my savings were going, I’d put in about 20 gees in there. So I had to think of a way to make income without getting employed. I went back into acting and did some extra roles until March, when I got a role with Naswa, to prank people on the streets.”

We both laugh out aloud. Benta continues, “But I had to be fired after a month because you’re not supposed to be known by people. I got 12 gees from acting there but I hated it!” Benta shakes her head.

“What was your worst experience?”

She thinks for a moment. “There was a time I was almost beaten up for a prank I’d pulled on a TV camera man because I kicked his tripod for his camera to shake. I had to ruuunnnn!”

I catch myself laughing then ask Benta, “I’m curious, how were they coming up with those pranks lakini?”

“They used to sit down and brainstorm, ‘this is what we’re going to do, we’ll wear a mask and prank like this…’ It was like a script.”

Benta survived on extra roles until August, when she got cast for a series on QTV called Mchungaji. You seen it? I haven’t. She played the role of a househelp. She still does.

I’m chatting Benta from her digs in Embakasi. It’s a bedsitter.

Earlier this week, when I’d called her up to set up the interview, she’d warned me that our equipment might not fit in there.

I snickered to myself because… because our ‘equipment’ consists of only these things: an Olympus camera (my little starter camera that Will would later tell me was only good for images, not video. I don’t know why that piece of truth broke my heart), a Sony camera for video borrowed from my kid brother (we don’t have it on this Friday afternoon because it’s at the repair shop – his SD card had jammed in the slot; I had to borrow one from my pal. Thankfully she lives enroute to Benta’s so we pitiad there to collect it. I’m going to keep it until the day she asks for it back, hehhe). We also use speed lights and a tripod still borrowed from my bro.

Craft It’s videos are being shot on borrowed equipment.

I only pray that we’re not running on borrowed time. Or a borrowed platform. Or borrowed views. Or borrowed ideas. Or, God forbid, a borrowed videographer (hey, Will).

In Emba, Benta asks me to call her when we get to the Kobil petrol station. She had said her place is huko interior, that it’s easier for her to come get us than dropping us a PIN for us to navigate to her.

It’s about 2.30 in the afternoon. Friday. It’s a hot day and I’m drained from the stuff I’ve had to get done since I got up that morning.

We get to her apartment building and Benta leads us up the stairs. Her TV is tuned to Big Brother.

“Is it any good?”

“Yeah, I’m addicted,” she titters, standing in front of the TV next to me. “But they took it to Nigeria so it’s different. They’re all Nigerians and they talk in that sheng of theirs, there are some things I can’t even understand.”

The scene is of two lovers, I suppose, in bed, with their cheeks on their pillows and their large-lipped cup mouths inches from each other. They’re speaking in that annoying way reality stars speak when they know they’re being watched by an audience, in an almost-scripted drone that stretches what should have been a quick convo into the pits of eternity. I could drive to tao and back and I’d still find them splitting the hairs on whatever they’re speaking to each other about.

I say to Benta, “The last one I followed was the one for kina Gaetano and, what was her name, his girlfriend, the one from Cape Town or something? Abby, yes, yes. Abby. Ha ha. I’ve never followed another one again.”

To the other corner of her digs is Benta’s workstation – her Typical sewing machine threaded to black, some tools scattered on and bags in different styles hanging by hooks on the wall above her, others are strewn on the couch. I can smell the glue she’s struggling to peel off her fingers.

Will is setting up our equipment. Me? I only need to put my voice recorder on the table and hit the record button and I’m good to go. Will preps for a shoot as a biker preps for a ride.

I ask Benta, “What are you making now?”

“This bag for a client.” She shows it to me. “It’s a bag pack so I need to put in the straps and the buckle and finish the inside lining. I’ve been making it for about a week, I’m selling it for one thousand, five hundred.”

Benta doesn’t say ‘1,500’ or ‘2, 5’ – she prefers to say the figures in words. I find that amusing. Like later, when she’s telling me about one of her earlier vintage bags she sold to Peter Nduati, she says, “It was thirteen thousand, five hundred shillings.”

“So it’s after you finish your week’s training with Kandu that you realized you needed a machine?” I sip more water.

“No, I knew machines were very cheap until I went to KIRDI and Kandu told me machines are verrrry expensive.” Benta pulls that ‘r’ so much I worry it’s going to tear in two. “Like to get a nice machine, like the ones they had, was 250K.”

“Define for me a ‘nice’ machine.”

“A nice machine is like a walking foot, because the needle walks, not like the other machines. And it can stitch heavy layers of leather. Plus the stitches are very defined and strong. Even this one I have is nice,” Benta slaps the body of her Typical machine, “and it was a bit affordable, it was 80K. Kandu misadvised me and I bought a machine for 78K, but it wasn’t for stitching leather, so I sold it after a few months. That was another mistake I made. I just got this one this year in February.”

Surprised, I ask, “So what were you using before you got it?”

“I used to stitch by hand. I stitched by hand for about two years, since… August 2016 to February 2018.”

I widen my eyes. “How do you hand stitch leather?!”

Benta giggles. “You,” she sighs as she attempts to explain it to me, “you–”

I interrupt her and say, “You’ll show us, actually, later, then Will will shoot it in the video.”

Benta nods. She shows me the tools she uses for hand stitching. She uses a very long and thick needle, she bought it for 10 bob from River Road (ideally, she says, a hand stitching needle should be blunt at the tip. Hers isn’t). The hand stitching thread is the one used for shoes.

She also uses a stainless steel rotary punch (it’s for making holes in the leather, for articles such as belts), a set of stainless steel punch tools and a wooden mallet (the wooden mallet is used with the punch to pierce holes into the leather, it’s these holes where the threads will go when the leather is being stitched together by hand). Benta imported these other tools from Japan.

I inspect the tools one by one. I ask, “So how long would it take you to make one bag using this hand stitching method?”

“Depending on the size, even for seven days. And that’s stitching the whole day – from morning, take a lunch break and relax, then in the afternoon til evening. It’s very tiring, you can’t go nonstop without taking a break. But I always worked with a schedule, I’d say like today I’ll work on the zipper, then tomorrow on the base, like that, like that until I finish.”

Benta shows me some of her earlier pieces, the ones where she exclusively used hand stitching. She also shows me her recent pieces, the ones with machine stitching. I can see the difference – the hand stitches are large, visible and slightly uneven; the machine ones are smaller and neater, barely visible and tighter.

She says, “But hand stitches last longer than machine stitches. I still do hand stitching for some clients who understand the value.”

See the difference between the two, in the image below.

Benta made her first sale in August 2016. It was a hair-on leather bag in colour black and white, and stitched by hand – it was boxed shape with a horn for the handle, a black and white horn. She sold it on Kilimani Mums Marketplace for Sh8,400. To some muhindi man who said he was buying it for his wife.

“How did this first sale make you feel?”

“I felt like I was the IT thing! Ha ha. After that I went to Thika and bought like 100 square feet of leather and I made 15 pieces of bags using hand stitching. It took me quite some time, about half a year. Then I took them to the flea market at Purdy Arms. I was very overconfident because I knew my bags were yeaaahhhh,” Benta giggles and bobs her head, “but nobody even looked at my bags twice, nobody bought anything and I didn’t understand why. I was selling them for like six gees, 10 gees. I used to look at what competition was pricing their bags then lowering my prices by a bit. Nowadays I don’t even look at what they price.

“Then last year [2017], I got an opportunity to train with an entrepreneurs program for free for six months. That’s where how learned how to scale up my business, work out the cost of production, prepare financials, marketing…. You know.”

“What’s its name?”

“The Mbugua Rose Foundation, it’s named after Uhuru’s nephew and his [nephew’s] fiancé, the ones who died at Westgate. And that’s where I met this woman called Mary Mukindia and she told me,” Benta takes on the accent of a rich, old, sophisticated woman, “‘Benta, I’d never buy your bags’. And I was like, ‘What?!’” Benta laughs and continues with the accent, “‘Have you ever seen a woman like me wearing pearl earrings carrying such bags?’ Ha ha. That was the first time someone told me the truth about my bags. And she also guided me, told me to go around the industry and the markets and see what types of bags people like.”

I laugh. I’m awfully thirsty, gosh. “Kwani what types of bags are these you had made?”

“They were colours, heh.” Benta laughs. “Green and red. Then the stitches were just bad, they were not proportional. I don’t even know what I was doing back then. So I came back and sat down to rethink my bags. I listened to her because she represented the target market I wanted to makes bags for.

“Her words changed everything for me. I started over. I rebranded to BagWorld Leather and deleted all the photos I’d uploaded to Facebook. Then I gave away the bags and sold some at a throwaway price.”

Benta sources her leather from Alpharama Tanneries, they’re based in Athi River.

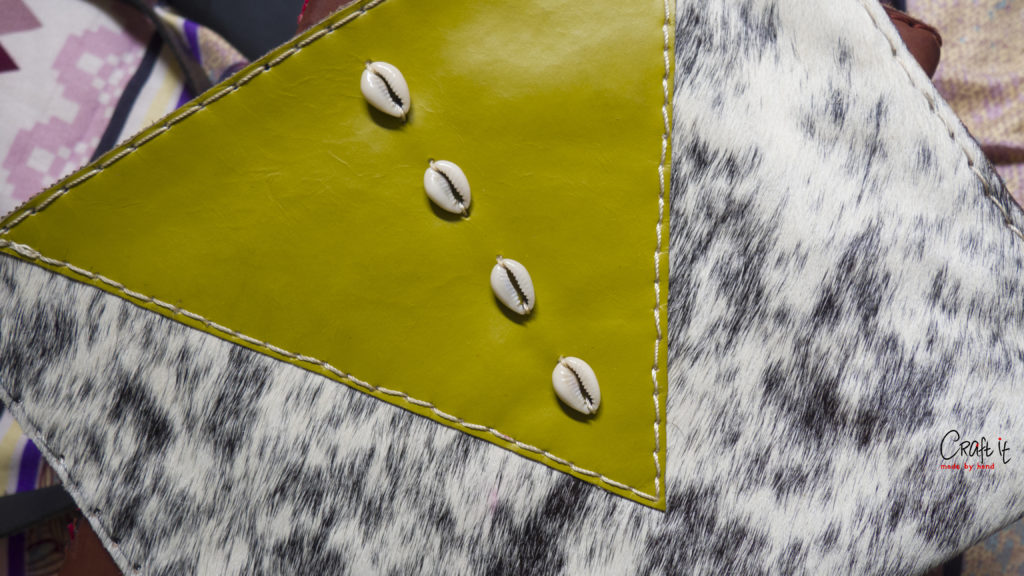

She buys leather of different kinds to meet the needs of her different clients. Hair-on leather is the one that still has the cow’s hair on it, the manyoya, it’s the most expensive per square foot but it’s not popular amongst Kenyans. Smooth cow belt leather is the cheapest per square meter and the most popular; its products are also cheaper.

Tanned leather comes in different colours like red, green and black. Lining leather is for the inside of the bag, costs about Sh145 per square foot. Vintage leather is also fairly pricey and the one Benta likes to work with the most; it’s heavy but feels smooth, suede-ish, to the touch.

The signature of her bags is the accessories on the bag’s body, the handcrafted bones and horns.

Benta tells me about some of the consistent contracts she has now with some companies across Nairobi. She also tells me about her plans to expand her workforce and her product portfolio. And about how she wants to work with physically challenged women.

“What have your new designs taught you as a craftsman?”

“That simple is everything. Kenyans want simple, so keep it simple.”

~

What BagWorld offers

Platinum products are those made from high-quality leather, brass fittings, heavy-cotton or leather lining

– Travel bags, handbags, sling bags, clutch bags, laptop bags and sleeves, backpacks: Between Sh3,500 and Sh15,000

– Belts, wallets, book covers, passport and driving license holders: Between Sh800 to Sh1,200

Gold products are those made from affordable leather, canvas or African print

– Travel bags, handbags, sling bags, clutch bags, laptop bags and sleeves, backpacks: Between Sh2,500 and Sh6,000

– Belts, wallets, book covers, passport and driving license holders: Between Sh350 to Sh650

Reach Benta

Phone number: 0724-635839

Facebook: BagWorld Leather

Email: wanguibenta@gmail.com

YouTube

Watch the video on our YouTube channel here >> Benta of BagWorld Leather

Photo credits: All photos by Aegean Will, for Craft It.

Image copyrights apply. None of these photos should be used elsewhere without the express permission of Craft It.

Hand stitched baguette bag in high-quality leather, accessorised with Ankara

Canvas and soft cow belt leather, hand stitched

Laptop sleeve made of tanned leather and accessorised with bones, machine stitched

Note the detail on the flaps and clasps

The inside of one her earlier pieces in hair-on leather. Note the quality of the lining

Bag pack in soft cow belt leather and Ankara. Machine stitched

Clutch bag accessorised with shells

Tanned leather, laptop bag for men

Tanned leather, office bag for the corporate woman

Loads of useful compartments in the corporate woman’s handbag, lined with Ankara

Benta’s logos are stitched in the insides